Lucera

Frederick II established a large Islamic community there, from which the city derived the name "Lucera dei Saraceni". The resident Jewish population was also numerous in the Middle Ages. Here a Sèfer Yosippòn was copied in 1472, now preserved in Paris, for a Jew who lived in Manfredonia.

Sannicandro Garganico

"From Melfi on a day’s journey we reach Ascoli: there are about forty Jews, the most important are Rabbi Consoli, his son-in-law Rabbi Tzèmah and Rabbi Yosèf." The town, the first in the current administrative borders of Puglia (at the time of Benjamin present-day Basilicata was part of Puglia too), is worth a visit for its centre rich in important monuments.

Ascoli Satriano

The history of the local community is unique. In the 1930s, Donato Manduzio, who aimed to restore the Jewish laws of the Old Testament, urged the progressive conversion of some of his fellow citizens to Judaism. Some of those who followed in his footsteps moved to Israel immediately after the creation of the State, while others remained in the town, where a small synagogue is still active today.

Siponto

From Benjamin’s narrative we learn indirect information about the famous Jewish academy of Siponto, whose members visited Baghdad; thanks to the scientific knowledge acquired in the East, they contributed to the development of the oldest medical faculty in Western Europe, the School of Salerno. The Jews from Siponto moved to Manfredonia.

Manfredonia

The community of this city, named after Frederick II’s son, Manfredi, underwent the conversion policy of the early Angevin age (late 13th century). For this reason, a considerable number of neophytes remained there with the benefit of special statutes until the 16th century.

Barletta

hanks to its port it was home to a large community in the late Middle Ages, increased by the massive number of refugees who arrived in the city after the expulsion from Spain in 1492. There are many archive documents related to Jewish merchants living in the city around present day Corso Cavour, once called via del Cambio (Money change street). Among them, the great Iberian intellectual Yitzhàq Abravanèl (1437-1508) lived there in the early 16th century, together with his son Yehudàh (ca. 1460 - after 1521), better known as Leone Ebreo, the author of one of the most widespread Renaissance works of aesthetics, Dialogues on love, composed in Italian, possibly in Barletta.

Bisceglie

In this sea-port, present-day travellers may still wander about the medieval Jewish neighbourhood, which is located in the area of the church of San Domenico. Its main street is called today “Strada Tevere”.

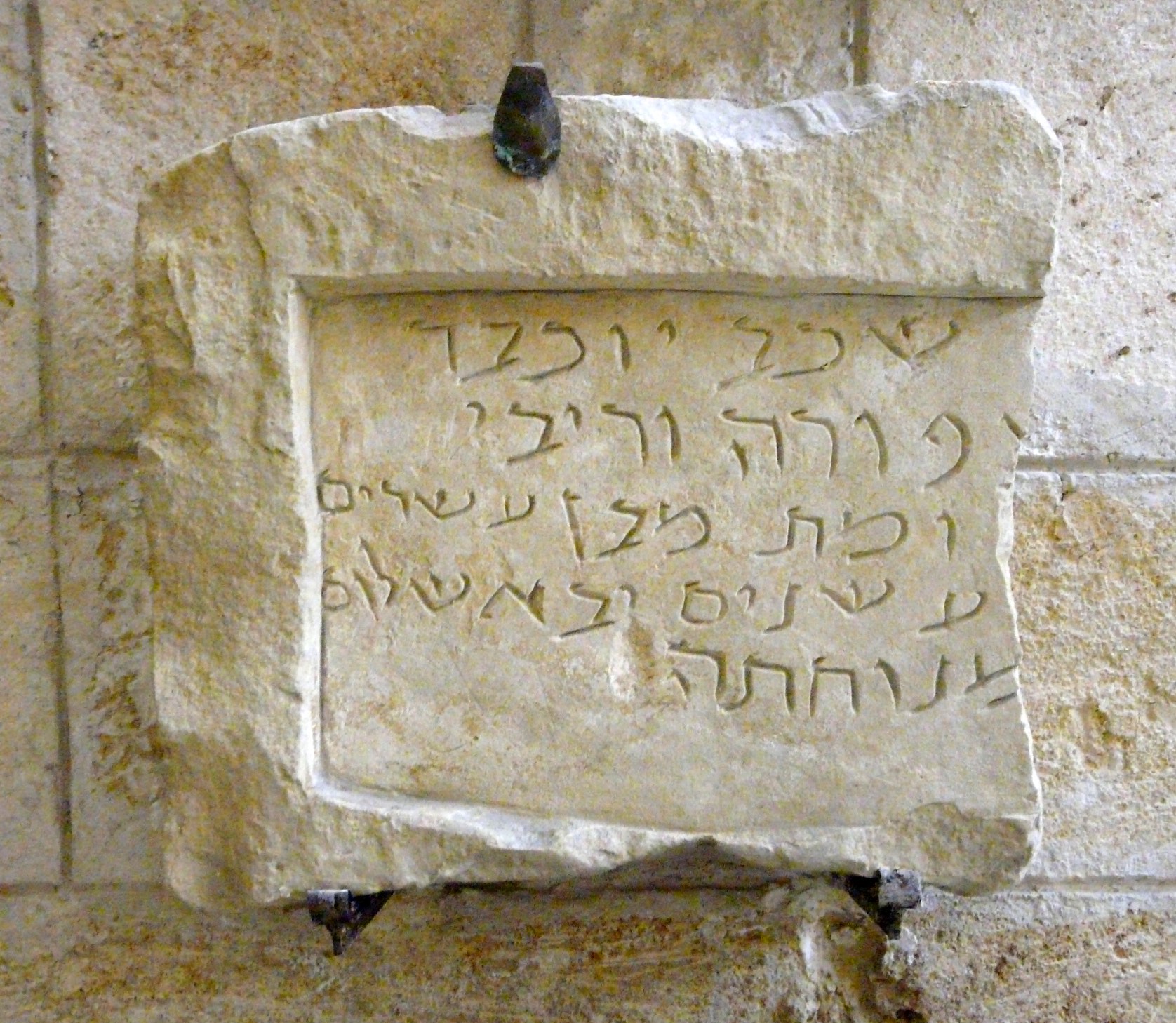

Trani

"In two days walk you arrive in Trani, located on the seashore. Thanks to its easily accessible port, it is a gathering place for all travellers to Jerusalem. It is a great and beautiful city, populated by about two hundred Jews, headed by Rabbi Eliyyàh, Rabbi Natàn the exegete, and Rabbi Ya’akòv." Trani still retains its beautiful medieval centre. Thanks to the traffic of pilgrims going to the Holy Land, Trani hosted a large community during the Norman-Swabian domination. Their number decreased during the Angevin rule and regained a significant role during the Aragonese domination (15th century) and until the 16th century expulsion. The street name "Via Giudea" recalls the ancient Jewish quarter, near the port. Do not miss the two 13th-century synagogues, entirely preserved in their architectural structure: Scola Nova and Scola Grande (scola = synagogue). Scola Nova, transformed into a church during the 13th century like the nearby Scola Grande, was regained to Jewish worship at the time of the recent reconstitution of a small local Jewish community. In the building the aròn ha-qòdesh (holy ark) in stone, the niche of the Jewish scrolls of liturgical use, is still visible. After decades of abandon, a careful restoration has made Scola Grande the main museum of Apulian Judaism (Museo Sinagoga Sant'Anna). Inside is kept the foundation stone, dated 1246. Various Jewish funerary inscriptions found near Trani have been transferred to the Museum, while others are still visible, relocated in some buildings of the historic centre.

Andria

The church of Santa Maria Mater Gratiae in Andria was probably built on the remains of a synagogue.

Bitonto

We know that an important Jewish school was active there in the fifteenth century of which information survives from educational works composed for the use of local students. The Calònimos family played a prominent role there.

Bari

"A day’s walk from Trani is Nicola di Bari, the great city destroyed by King William of Sicily. The place is now in ruins and neither Jews nor Christians reside there." At the time of Benjamin, the city was in a very poor condition, following the destruction ordered by William “the Evil”. However, its fame in the previous and subsequent period never faded, as can be seen from the saying mentioned in the preface: "From Bari will come forth the Torah...". The local rabbinical schools were very important, and some local poets produced liturgical hymns between the 9th and 11th centuries. A Jewish inscription dating to the 14th century is the only remain from a synagogue in Bari, and it is preserved in a private house in San Sabino street, inside the ancient Giudecca district, near the Cathedral. A plaque recently placed outside the Effrem palace shows that there was another synagogue. Jewish families converted during the 16th century, built elegant palaces in the historic centre of the city that are still visible (Zizzi, from 'Azìz; Calò, from Calònimos). The tombstones currently on display (some in reproduction) inside the Swabian Castle come from the area of Bari. A small Jewish presence was revived before the Second World War. Some recent tombs are visible in the cemetery of Bari.

Altamura

One of the four districts of the centre is traditionally considered the ancient Giudecca.

Gravina

The little church of San Bartolomeo may have been built on the site of the ancient synagogue. A Jewish inscription of the Norman Age gives us some information about it. Inside the cathedral various decorations depict a menorah. Tradition states that the restoration of the elegant Norman building took place between the 15th and 16th centuries, thanks to the funding of a local Jew.

Polignano

As in other Apulian centres, also in Polignano there was a Giudecca. Traces of the old Jewish district remain in the place names. The current street Innocente Tanese was called "via della Giudea". A building in this street would have been the synagogue. Among the families who lived longer in the neighbourhood, it seems that the Bellipario were Jews, already converted during the Angevin Age: their surname refers to the typically Jewish activity of leather tanning.

Monopoli

Many Jews settled there under the protection of the Republic of Venice between the 15th and 16th centuries, including Yitzhàq Abravanèl, already mentioned, and Hayyìm Yonàh, expelled from his native Sicily in 1493 together with other Jews. He supervised a Beit Din (rabbinical court) between Trani and Monopoli, providing extensive documentation in some legal responsa, now kept in Florence. Hayyìm gives us information about the local communities and recalls the philosophy lessons taught by Abravanèl, who wrote during the 15th century in Monopoli three messianic treatises in which he held that the Redeemer of Israel would come in 1503. In Monopoli remains the memory of a Jewish academy that seems more like the product of the activity of Christian scholars of the Renaissance.

Massafra

A Hebrew manuscript was copied there during the 15th century. The local community seems to have been closely associated with the activity of fabrics washing.

Taranto

"From here it takes a day and a half to get to Taranto, which is part of the kingdom of Calabria. It is a large city, populated by Greeks and about three hundred Jews. Among the many scholars are Rabbi Meìr, Rabbi Natàn and Rabbi Yisraèl." Twenty-six funerary inscriptions in Hebrew, Latin and Greek, dating to between the 4th and 5th centuries, are now preserved at the National Archaeological Museum (MARTA). These stones confirm the importance of the community, which was founded, according to tradition, by a colony of Jews deported by Titus and committed mainly to commercial activities. The settlements were possibly located in the old city, while the cemetery area was outside the urban area. A recent building is commonly considered to have been used as a synagogue.

Manduria

There is no reliable information about the Jewish presence in Casalnovo (the present Manduria) during the 13th - 15th centuries, while it was significant in the early 16th century until the expulsions in 1541. The Jewish ghetto (“Ghetto degli Ebrei”) dates back to the second half of the 17th century, probably aimed at hosting converted Jewish families. The district is located in front of the main church and is delimited by three entrances that were closed at sunset, following the 16th century church regulations. A building, traditionally referred to as a synagogue, has a facade with rosettes; another one is said to have been the “Rabbi’s house".

Oria

Located on a strategic hill next to the Via Appia, between the 7th and the 9th - 10th centuries the town hosted an important Jewish community who lived in the eastern part of the city, near the gate still called "Porta degli Ebrei” (Jewish Gate). An early medieval Jewish cemetery (8th - 9th centuries CE) has been found on a hill a few hundred meters far from the city gate. In the Municipal Library one of the most beautiful funerary stonesof the region is visible, dating back to the 6th or 8th centuries, with writings in Hebrew and Latin, in memory of Hanna, daughter of Iuliu (= Yo'èl). Another stele with a menorah is preserved inside the beautiful Fedrick II's castle. The square in front of the Jewish Gate (where a large menorah was recently placed) was named after Shabbetày ben Avrahàm Donnolo (913 - ca. 973), a distinguished physician and philosopher, a prominent figure of medieval Judaism. Local tradition identifies a small building in the Giudecca with a synagogue. The memories of the community of Oria in the Byzantine age are largely known thanks to the splendid chronicle of the Sèfer yuhasìn (Book of genealogies), composed in 1054 by a descendant of local Jews resident in Capua, Ahima'àtz ben Palti'él.

Brindisi

"A day’s walk separates Taranto from Brindisi: located on the seashore, the city welcomes a dozen Jewish dyers." The first landing point of the numerous Jews coming from the Land of Israel at the time of the destruction of the Second Temple, the local community was still flourishing in the 9th century, when three important funerary inscriptions in Hebrew were carved, today kept at the Provincial Archaeological Museum. A street retains the name Via Giudea. The synagogue, transformed into a church, was ruined already in the middle of the 16th century.

Lecce

The mention of a Lecce Jewish dignitary is found in the oldest Jewish funerary inscription dated in the catacombs of Venosa (521 EV). Information about a local community dates back to the 14th century, when the city flourished under the protection of the Del Balzo Orsini family. In the Aragonese period the Jewish settlement was particularly significant: most of the Jews were of Catalan and Provençal origin but there were also numerous Balkan Jews. The giudecca occupied a fairly large area near the Porta di San Martino (St. Martin’s Gate) and the Piazza dei Mercanti (Traders’ Market, now Piazza Sant'Oronzo). Jews played a significant role in the city’s economy, engaged in industrial activities of dyeing and tanning of hides, cloth and metal processing, lending and commercial mediation. A synagogue was to be located in the site of present-day Personè Palace, where the Jewish Museum is located. Of the building remains a fifteenth-century Jewish inscription reused in the building of nearby Adorno palace. Numerous Hebrew manuscripts were copied in Lecce during the 15th century, particularly for the De Balmes family.

Copertino

The Borgo Scialò (perhaps connected to shalòm, "peace") would be the last area inhabited by a community that became significant especially during the 15th century. The area of the giudecca occupied a central position, near the Market Square (today Piazza del Popolo), where the synagogue was located, on which the church and the convent of the Clarisse were later built. One of the oldest documents preserved in the Salento dialect is a correspondence (1392-1415) between a Copertinese Jew, Shabbetày Russo, and a Christian Venetian merchant, Biagio Dolfin, who had created a trading company.

Soleto

The Romanesque-Gothic church of Santo Stefano combines elements of the Latin and Greek church in the beautiful cycle of frescoes that entirely covers the walls, dating from the late 14th and early 15th centuries: the rich decoration shows us the perception of the Jews in the eyes of the local Christian population: they were marked by the "signs of infamy" typical of the time (the so-called wheel). The local community may have resided near present-day Rua Catalana. Other centres of the “Grecìa" (Greek-speakin) area testify in the toponymy to the ancient presence of giudecche (Sternatia, Carpignano etc.)

Galatina

In the 15th century Jews had to reside mainly in the area of present-day Via Zimara. An echo of the local Jewish presence shines through the magnificent Giotto-style frescoes in the Basilica of Santa Caterina d'Alessandria, built by the Del Balzo Orsini between 1383 and 1391. In the Christological cycle of the early 15th century Jewish characters can be clearly singled out by their "derogatory" physical features that draw inspiration from French iconographic models.

Nardò

This city enjoyed a remarkable importance in the 15th century, when it was populated by a large Jewish community that lived in the district of San Paolo, close to the walls and a short distance from the gate opened towards Lecce. Local Jews were engaged in trade by sea and mainly practiced the activity of dyers and tanners of skins. It is a tradition that the synagogue was built on the site of the sacristy of the church of Sant'Antonio da Padova and it was used by the local feudal lords as a funerary chapel. A document dated 1573 provides information about the location of the Jewish cemetery, located outside the area of the walls, not far from the Giudecca, near the Asso canal.

Otranto

“In altri due giorni si giunge ad Otranto, sulla riva del mare greco. Vi risiedono circa cinquecento ebrei, con a capo rabbi Menahèm, rabbi Kalèv, rabbi Meìr e rabbi Malì.” Data la sua funzione di porto collegamento con il Mediterraneo orientale, la città fu sede di un’importante comunità da epoca romana, come attestano le memorie medievali. Il più antico documento che attesta la presenza di ebrei ad Otranto è costituito da una iscrizione funeraria di una giovane, Glyka, in greco e in ebraico, databile al III sec. EV., decorata da una menorà, oggi conservata presso l'attuale Museo Diocesano. Nell’alto Medioevo vi fiorì una scuola che annoverava vari poeti liturgici; nello stesso periodo nel locale scriptoriu furono copiati importanti manoscritti, oggi conservati in varie biblioteche in Italia e all’estero; ricordiamo ancora una volta il famoso detto “da Bari uscirà la Torà e la Parola del Signore da Otranto”

Gallipoli

We know that the Giudecca was located outside the center of the island, in the area that still takes its name from the Jewish settlement. For a long time the city was considered, by the Salento Jews, a sort of safe haven, a place of shelter when elsewhere, persecution raged.

Specchia

In this small city lived in the early 15th century the physician Davìd Nèzer Zahàv, who also lived in Lecce and Corfu. In 1415 he copied and decorated in Specchia a copy of a Hebrew version of an Arabic text of surgery. His beautiful manuscript is preserved today in Vienna.

Alessano

The giudecca was next to the Porta di S. Maria (St. Mary’s Gate), not far from the Castle. The area, which cannot be dated before the 15th century, has an internal courtyard (today’s Piazza O. Costa), with an access arch still well preserved.