“From Bari will come forth the Torah and the word of the Lord from Otranto”

Two thousand years of Jewish presence in Puglia

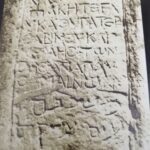

Jews in Apulia are documented at least since the Roman imperial period: this makes the Adriatic region one of the oldest Jewish settlements of the whole Western European diaspora. According to the Sèfer Yosippòn (Book of Joseph), a Hebrew chronicle possibly composed in Puglia in the 10th century, after the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem (around 70 CE), "Tito brought about five thousand deportees to Taranto, Otranto and other cities in Puglia.” They were members of the highest priestly families of the Land of Israel. Although the Hebrew tradition holds the first Jewish groups as slaves, it seems that many of the exiles managed to integrate in the cosmopolitan ports of Puglia. They were mostly traders, who kept contacts with the Mediterranean East and the northern African shore, but they also carried out occupations often associated with the textile industry and ceramic production; some others practised important public offices in the various municipia (the Roman townships). The Jewish catacombs of Venosa preserve the oldest surviving sepulchral epigraphs in Hebrew: they prove the tendency of the Jewish population to move, especially along the main Roman routes, which stayed in use throughout the Middle Ages. Funerary inscriptions, dating back to the 6th century, show that the local Jewish population used Latin as a language of communication while they used names derived from the Biblical tradition associated with other non-Jewish onomastics. Jewish teachers moved from the Apulian coasts and spread their knowledge throughout the Mediterranean area, so much so that in the northern Europe of the 12th century it was said, paraphrasing a verse of Isaiah, “From Bari will come forth the Torah and the word of the Lord from Otranto.” Important Jewish schools were still active in the 15th century in Bitonto, Trani, Barletta, Monopoli and Otranto, where many refugees moved after the forced conversions in Spain and Provence. Despite the changing conditions of tolerance imposed by the various regimes that succeeded one another in the Adriatic region, the Jewish presence in Puglia did not stop until the definitive expulsions of the 16th century, when southern Italy became part of the Habsburg dominions of Spain. The obligation to choose between exile or baptism led to a split between those who preferred to abandon their belongings rather than renounce the faith of their ancestors and those who accepted the impositions. Within a few generations almost all traces of their centuries-old presence were erased. Synagogues and community buildings were demolished or converted into churches and convents, liturgical scrolls, scientific manuscripts and other documents were destroyed, religious objects were melted or sold for their intrinsic value. What survived of this centuries-old presence were the holdings that the refugees managed to bring with them, along with the recollection of Apulian life and other memories of diasporas in the centres where they moved: Venice, Corfu, Mainland Greece, Constantinople... There the cult and the languages of the local Jews experienced the influence of Apulian traditions, still witnessed today in Corfu, where the present-day community calls itself Apulian or in Thessaloniki, where until the tragedy of the Shoah there was a synagogue named "old Puglia", another one named "new Puglia" and, until 1960, there was the building of the congregation named "Otranto". Traces of Apulian Jewish habits remain vivid in the works composed in the region and in the surviving Jewish manuscripts that were copied and that are still preserved in public and private libraries around the world. After centuries of oblivion, the Jewish presence returned to the Adriatic region with the opening of refugee camps that housed Jewish survivors of the Shoah in the aftermath of WWII. Those refugees, who looked for a welcoming land in which to start a normal life after the tragedies suffered, moved from Puglia, often illegally, to reach the Land of Israel.

Despite the damnatio memoriae of the modern age, in Puglia there are still places that make it an essential destination for international Jewish tourism. Even today, an Apulian Jewish itinerary takes us along the ancient Roman-built routes, in particular the Via Appia and the Via Traiana, on the footsteps of pilgrims and merchants heading towards Rome or Israel. Benjamin of Tudela, one of the most renowned medieval Jewish travellers, described in his Travel Book the steps of his journey in 12th century Apulia. From his lively narrative (here in italics) our itinerary begins, enriched with numerous steps that will make today’s traveller a modern pilgrim of memory.

Refugee camps in Salento.

At the end of the Second World War, all over Europe a need was felt to help the large number of Jews who had lost citizenship of their countries of origin and who were, by and large, survivors of labour and extermination camps. With such an aim, the Allied powers, supported by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), established transit camps especially in Germany, Austria and Italy. These camps were created to allow refugees to recover before embarking on the journey back to their old or on to their new destinations. For most of the Jews who lived in these DP (Displaced Persons) Camps, the hope was to reach a place where they could live without having to comply with the restrictions that Jewish minorities had had to accept, and where they could recreate a life worthy of the name after the hardships they had suffered in Europe. Italy played a central role in the illegal emigration of thousands of Jewish refugees to Palestine, so much so that it was called the "Zion Gate". Starting from September 1943, several waves of Jewish refugees of various nationalities converged on Puglia, which had just been liberated, but was still suffering from the war. From 1944 to the creation of the State of Israel, there were DP Camps in Trani, Barletta, and Bari. In the countryside near Gioia del Colle there is still a large farm, the "Casina rossa” (little red house) that hosted many refugees after the war. In Salento, the seaside resorts of Santa Maria al Bagno (CAMP 34), Santa Maria di Leuca (CAMP 35), Santa Cesarea Terme (CAMP 36) and Tricase Porto (CAMP 39) were selected to shelter refugees, who were housed mainly in the summer villas of the local bourgeoisie. This system remained operational from 1944 to 1947. The memories of the refugees and the hospitality of the local population are the focus of the Museum of Memory and Welcome at Santa Maria al Bagno. The centrepiece of the museum is three murals painted in 1946 by a Romanian Shoah survivor. So, for a short time, the Jews repopulated the region that had hosted them in the past. From these Puglian coasts the descendants of the former exiles of Israel finally managed to return to their ancient land as free men and women.